The Coventry and Pyke Families in World War I.

Rob Lamont has given us some information about his relatives who have featured in my First World War items in AboutMyArea.

Rob’s grandfather was Bob Coventry; Bob and his brother Frank, and sister Nora from Brook Street were all performing, as children, in the Presbyterian Sunday School concert in February 1915 (See Week 30).

In March 1914 the King and Queen made a visit to Wirral, and a photograph of them on Hooton Station shows leader of the Neston Boys Brigade, William Molyneux Coventry, Rob’s great-grandfather, greeting the King.

Bob and Frank are in the front row of the boys. Accompanying the King is Sir William Lever (later Lord Leverhulme) (also in top hat).

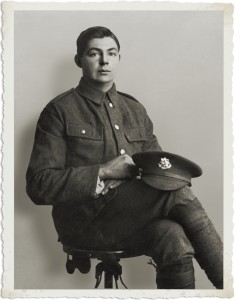

Rob also tells us about his great-uncle John Pyke

John Pyke was the eldest son of James and Elizabeth Pyke. He was born on 1 April 1894. He had an elder sister, Mary, two younger brothers, George and Tom, and two younger sisters, Margaret and Sarah. The family lived in Liverpool Road, Neston.

John was interested in cars and after leaving school found work in a local motor works as an apprentice engineer. He learnt to drive and by the start of The Great War, at the age of 20, he had established himself as chauffeur to Neston’s general practitioner, Dr. Lewis Grant.

Along with other young men from Neston, John answered the call to war and enlisted in the army on 1 September 1914 with the 8th (Service) Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment. The regiment had only recently been formed at Chester on 12 August 1914 as part of K1 and came under orders of 40th Brigade, 13th (Western) Division.

On 3 September 1914, John was posted to Tidworth to join the regiment for basic training, and on 14 September the regiment moved to Chisledon. From there, in February 1915, the regiment moved to Pirbright and on 26 June 1915 embarked for Egypt and thence to Gallipoli.

The Gallipoli Campaign of World War I took place on the Gallipoli peninsula (Gelibolu in modern Turkey) in the Ottoman Empire between 25 April 1915 and 9 January 1916. The conditions at Gallipoli were some of the worst of the whole war; the extreme weather caused widespread sickness and sometimes death. Swarms of flies were a constant presence in the trenches, mainly due to the many dead.

As a private in ‘The Cheshires’, John fought at Gallipoli but, like many others, found that the climate and conditions affected him badly. He suffered from dysentery and diarrhoea and was taken into hospital at Mudros on 7 August 1915. Mudros comprised a small Greek port on the Mediterranean island of Lemnos; it was only 30 miles away from the scene of the battle in the Dardanelles and, as such, was ideal for transferring men and supplies.

Scorching heat during summer gave way to torrential autumn rain and a freezing winter. Almost all soldiers suffered from dysentery. A blizzard in November 1915 caused some 160,000 cases of frostbite, and froze 280 men to death. During the blistering summer months clean water became a limited resource and had to be strictly rationed.

By 28 August 1915 John was considered well enough to be discharged from hospital and returned to the Gallipoli peninsula. At that time new offensives and landings were launched along the peninsula to try and break the stalemate. Fresh troops had been brought in finally to try to defeat the Turks, but these offensives only resulted in even more devastating losses and the deadlock returned.

Unfortunately for John the dysentery returned, and he was again hospitalised on 28 September, having fought for one month. This time, however, Mudros had been abandoned as it was too small to cope with the huge numbers requiring treatment. So John was taken to the hospital in Cairo. This time the bout was more severe, and he remained there until 20 November 1915. At this time the British generals had decided to withdraw from Gallipoli, so John stayed in Egypt at Alexandria where he was engaged in the defence of the Suez Canal.

He was there for Christmas 1915, but more troops were needed to help lift the siege of the garrison at Kut-al-Amara in Mesopotamia and on Valentine’s Day 1916 he embarked with what was left of his regiment from Port Said bound for Basra. The journey to Basra by sea took 14 days on “HMT Umballa”, and upon arrival, John was barracked in the area prior to the 220-mile march north as part of Lieutenant-General Aylmer’s Tigris Force.

The attempt to relieve Kut was doomed to failure, mainly due to poor planning and decisions by Aylmer. The Turks had built ramparts up to 25 feet high in places to protect their positions. This became known as the Dujaila Redoubt. Despite delays, the British and Indian troops were in position to attack just before dawn on 8 March 1916. The Indians pushed forward to find very little resistance, but instead of acting upon this, Aylmer ordered them back and delayed the full attack for a further three hours. All surprise was lost and in the bayonet charge that followed John was wounded in his right arm.

Slowly but surely, the Turkish battalions counter-attacked with bayonets and grenades, which were in short supply on the British side, forcing them to retreat in the early evening. Through the night, the British forces fell back to a rendezvous position approximately 8,000 yards from the Dujaila position. When no counter-attack materialized from the Dujaila, Aylmer ordered his troops to retreat across the River Tigris, thus ending the battle.

John was hospitalised on 9 March with his arm injury, but it was not a too serious and he managed to write home saying that he had been slightly wounded, and that by the time his parents received the letter he should be well on the road to recovery. He was discharged from hospital on 23 April 1916 and returned to duties.

By this time the British Divisions serving in Mesopotamia were in a sorry and weakened state. Sickness was rife and nearly every soldier had suffered at some time from dysentery; poor rations had also brought a bout of scurvy amongst the troops, and at the beginning of May there had been an outbreak of cholera. Temperatures in the shade of over 45 degrees Celsius were common; the scorching wind, blowing like a blast furnace had burned and rasped skin unaccustomed to a tropical climate.

To add to the Tommies’ miseries were the flies, which fed off the dead of ‘No Man’s Land’. Apart from the diseases, which they had undoubtedly carried and spread, the discomfort of their presence was almost unbearable. The air was filled with their buzzing and every man carried his own swarm, for they settled on every portion of his anatomy where a hand could not reach to brush them off. In addition, every cooking pot, dish, and every scrap of food became black with them. The helpless sick and wounded suffered the most. Without mosquito nets and with very few tents one can only imagine the plight they were in.

As a result of the poor conditions, John succumbed to cholera, and sometime in May he was taken into the cholera hospital at Filayish. He died there on 22 May 1916 at the age of 22 years.

John is buried in the Amarah War Cemetery in present-day Iraq. Uncle “Johnny” was my great-uncle (my Nan’s brother) on my mother’s side.

Additional information from the Editor:

The Neston Victoria Jubilee Lodge was a branch of the popular Loyal Order of Ancient Shepherds, a male friendly society that flourished in the town and had an annual walk that rivaled the Ladies’ Club walk.

Private John Pyke had been a member for six years when, suffering from cholera, he died in hospital in Filayish, Iraq in late May 1916, aged 22, whilst serving in the Gallipoli campaign. It was said that around sixty of the Neston ‘Shepherds’ were serving, and John was the first to die.

A memorial service was held for him in Neston Parish Church at the end of July, attended by over sixty of the other local Brothers, who gathered at the Town Hall with their crooks draped with crepe and walked to the church for the service, and then returned to the Town Hall where Brother Cottrell paid tributes.